El Nino Explained

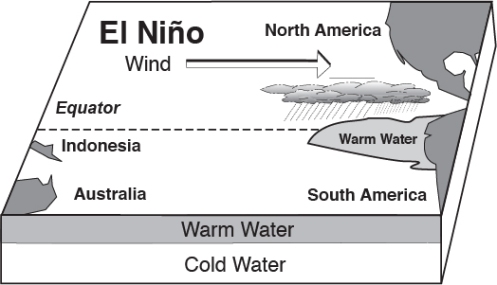

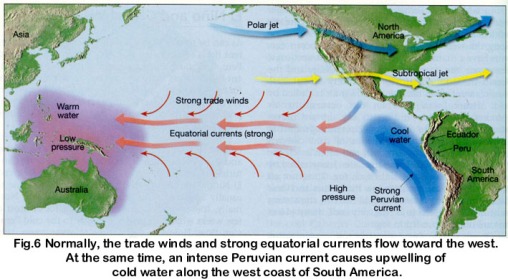

Every three to five years, driven by a reversal in the trade winds, an El Niño, a huge bulge of warm water under a blanket of tropical storms, hits the western most extension of South America, burying the cool Humboldt Current and dropping heavy rains on Peru and Ecuador, often around Christmas–hence the name El Niño (the boy), in honor of the Christ Child.

El Niño continues to gain strength in the Pacific Ocean, climate experts said, with unusually wet conditions expected to hit California between January and March — and perhaps into May. Among these consequences are increased rainfall across the southern tier of the US and in Peru, which has caused destructive flooding, and drought in the West Pacific, sometimes associated with devastating brush fires in Australia. Observations of conditions in the tropical Pacific are considered essential for the prediction of short term (a few months to 1 year) climate variations.

“January and February are just around the corner. If you think you should make preparations, get off the couch and do it now. These storms are imminent,” said Bill Patzert, a climatologist for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Canada Flintridge. “El Niño is here. And it is huge…. At this point, we’re just waiting for the impacts in California.”

The National Weather Service‘s Climate Prediction Center said El Niño is already strong and mature, and is forecast to continue gaining strength. It is expected to be among the three strongest on record since 1950.

“Generally, El Niño doesn’t peak in California until January, February and March,” Patzert said. “That’s when Californians should expect mudslides, heavy rainfall, one storm after another like a conveyor belt.”

On Nov. 4, sea surface temperatures in a benchmark area of the Pacific Ocean west of Peru hit 5 degrees Fahrenheit above average, outpacing the abnormally warm temperatures seen at this time of year in 1997, which developed into the strongest El Niño on record.

Patzert said one of the upsides in the forecast is epic surfing. Past El Niños have brought winters that went down in surfing history, and “it was one great set after another,” he said. “But the other side of epic surf is battered beach communities. That’s the flip side of it. The epic surf years also meant that beach communities were battered from Northern to Southern California.”

All info taken from the internet in so many different spots that I can’t even list them. None of it is our own. We aren’t this smart.